Futures contracts can sound intimidating to new traders, but they are essentially agreements about trades in the future. In a futures contract, two parties agree today on a price to buy or sell something at a future date. This allows people to plan ahead or speculate on price changes without immediately exchanging the asset. In this beginner’s guide, we’ll break down what futures contracts are, how they work, and why traders use them. We’ll also compare futures to spot trading, discuss speculation vs. hedging, and explain why futures are popular in financial markets – all in a friendly, easy-to-understand way.

What Is a Futures Contract?

A futures contract is a standardized agreement to buy or sell an underlying asset at a predetermined price on a specific future date. These contracts usually trade on exchanges, which means the terms (like the asset quantity and quality) are standardized and enforced by the exchange. In simple terms, a futures contract locks in a price now for a transaction that will happen later. The underlying asset could be anything from a commodity like oil or wheat to a financial asset like a stock index or currency.

Futures contracts were originally created for commodity producers and consumers to lock in prices and reduce uncertainty. For example, a farmer could agree in advance to sell a crop at a set price for future delivery, protecting against the risk of prices dropping at harvest time. Today, futures exist for a wide range of physical and financial assets – not just crops. You can find futures contracts on metals (gold, silver), energy products (oil, natural gas), stock market indices (S&P 500, NASDAQ), currencies (EUR/USD), interest rates, and even cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. No matter the asset, all futures contracts work on the same principle: an obligation for the buyer to purchase and the seller to deliver the asset at the agreed price on the future date.

Key Characteristics: Futures are traded on exchanges (like the CME, ICE, or Eurex) with standardized terms. Unlike private forward contracts, futures exchanges provide transparency and regulation, reducing the risk of default. Each contract specifies the exact amount of the asset (e.g. 5,000 bushels of corn, 100 barrels of oil) and the delivery month. This standardization makes futures easy to trade as you don’t have to find a specific counterparty, which means anyone in the market can take the other side of your trade.

How Do Futures Contracts Work?

When you trade futures, you’re not paying the full value of the asset upfront as you would in a spot trade. Instead, you post margin – a fraction of the contract’s value – as a good-faith deposit. This margin might be only a few percent of the total contract value, allowing you to control a large amount of the asset with relatively little money down.

For example, if a gold futures contract represents 100 ounces of gold, and gold is $3,000 per ounce (so $300,000 value), you might only need to put up say $15,000 as margin to enter the trade. It’s important to remember that this leverage is a double-edged sword: it can amplify gains (since a small price move on a large contract can mean big profit relative to your margin), but it also amplifies losses – if the price moves against you, your losses accumulate faster relative to your initial outlay.

Once you’ve entered a futures contract (either by buying to go “long” or selling to go “short,” which we’ll explain shortly), the price will continuously fluctuate with the market. You can exit the position anytime before the expiration by taking an opposite trade. For instance, if you bought one oil futures contract, you can close your position by selling one oil futures contract (with the same expiration) at the current market price. Your profit or loss will be the difference between the price you entered and the price you exited. In fact, the vast majority of futures positions are closed out before expiration – only an estimated 3–7% of futures contracts ever end with actual delivery of the asset. This means most traders use futures just to trade price movements, not to swap physical goods.

To illustrate how a futures trade works, let’s use a simple example: Imagine it’s January and oil is trading at $55 per barrel. You believe oil prices will rise by the summer. You buy a futures contract for 1,000 barrels of oil at $55, for delivery in June. You don’t pay $55 × 1,000 upfront; you maybe post ~$5,000 margin. By April, suppose oil has indeed risen and the June oil contract is now trading at $60. You could sell (close) your futures position at $60. The price went from $55 to $60, a difference of $5 per barrel. On 1,000 barrels, that’s a $5,000 profit (minus any fees) for you. If instead oil had fallen to $50 and you closed the trade, you’d have a $5,000 loss. This example shows both the leverage (controlling $55,000 worth of oil with a small margin) and the obligation – you must either close the trade before expiry or be ready to settle at expiration.

Futures vs. Spot Trading: Key Differences

It’s helpful to understand how futures trading differs from spot trading (buying or selling the asset for immediate delivery). Here are some key differences:

- Timing of Delivery: In spot markets, the transaction happens “on the spot” – you pay cash now and receive the asset now (or within a couple of days for many markets). In futures markets, the transaction (delivery of the asset or cash settlement) is set for a future date as specified by the contract. Essentially, spot = now, futures = later.

- Ownership: When you purchase in the spot market, you immediately own the asset outright. With futures, you own a contract – a claim to buy or sell in the future – not the asset itself until the contract expires or is exercised. For example, buying gold in the spot market gets you actual gold (or a claim to it in an account). Buying a gold futures contract gives you exposure to gold’s price movements, but you won’t own physical gold unless you hold the contract to delivery.

- Leverage and Capital: Spot trading typically requires paying the full price of the asset. If you want to buy 1 Bitcoin on a spot exchange and it’s $100,000, you need $100,000. Futures trading, on the other hand, uses margin and leverage – you might only need to put up a small percentage of the full contract value to open a position. This capital efficiency is a big draw of futures.

- Ability to Go Short: In spot markets, profiting from a price drop (short selling) can be complicated or restricted – often you have to borrow the asset or use special margin arrangements. In futures markets, going short is as simple as going long. You can sell a futures contract to bet on a price decline just as easily as buying to bet on a rise, with no need to own the asset first. This gives traders flexibility to profit in both directions and also to hedge (more on hedging soon).

- Standardization: Spot trades can usually be for any amount the buyer and seller agree on (e.g. you can buy 1.2345 ETH on a crypto exchange). Futures contracts come in set standard sizes (lot sizes) defined by the exchange (e.g. one oil futures contract = 1,000 barrels). You can only trade whole contracts (though some markets offer “mini” or “micro” contracts for smaller traders). Futures also have set expiration dates, whereas spot assets can be held indefinitely.

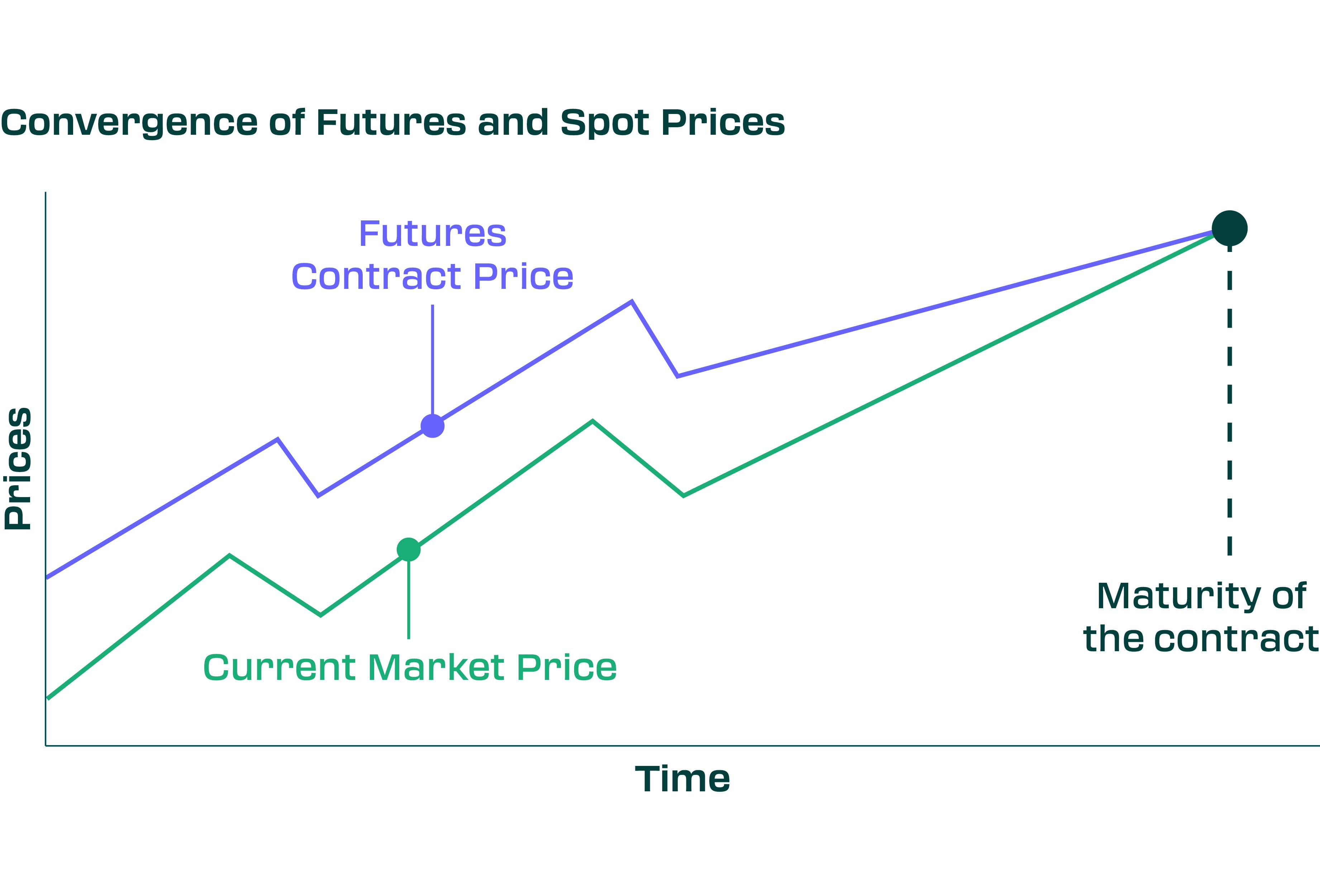

- Pricing: The price of a futures contract is linked to the spot price but can differ due to factors like storage costs, interest rates, or expectations of future supply and demand. For example, if it costs money to store a commodity or if interest rates are high, a futures price for delivery in six months might be higher than the current spot price. Conversely, sometimes futures trade lower than spot (in markets expecting price declines or with benefits to holding the physical asset). The spot price is determined by immediate supply/demand, while the futures price factors in cost of carry and future expectations. In essence, futures prices converge to the spot price by the time the contract expires.

Another important distinction between futures and spot markets is how their prices behave over time. While the two prices are closely related, they’re not always the same. Futures prices often trade above or below the spot price depending on market expectations, storage costs, and interest rates. However, as the contract approaches its expiry date, the two prices tend to converge.

In summary, futures introduce the elements of time and leverage into trading. They allow trading on future expectations with less capital, but with additional complexity (margin management and expirations) that spot trading doesn’t have.

Why Do Traders Use Futures?

Traders and investors use futures for two main purposes: speculation and hedging. In other words, some are trying to make profits from price changes, while others are trying to reduce risk from price changes. Let’s look at each role:

Speculation: Betting on Price Movements

Speculators use futures to try to profit from market fluctuations. They have no intention of delivering or receiving the actual asset; they just want to make money on price changes. Because futures allow high leverage and easy short or long positions, they are attractive for speculation. A speculator might analyze the market and predict, for example, that the price of corn will go up in the next three months due to an expected poor harvest. Instead of buying tons of physical corn, the speculator can buy corn futures contracts now. If the corn price indeed rises, the futures price will rise as well, and the speculator can sell the contract for a profit before it expires. On the flip side, if the speculator thinks crude oil prices will drop due to a supply glut, they could short an oil futures contract now and buy it back later at a lower price if oil falls, profiting from the decline.

Speculators are drawn to futures because of the potential for outsized returns on a relatively small investment (thanks to leverage). For example, controlling $100,000 worth of an asset with a $5,000 margin can yield great percentage gains on that $5,000 if the price moves favorably. Of course, this comes with high risk – speculators can also lose more than they put in if they’re on the wrong side of a big price swing. Still, futures markets have many active speculators providing liquidity. Their trading helps make the market efficient, and they’re essentially taking on the price risk that hedgers want to avoid.

Hedging: Protecting Against Unfavorable Price Changes

Hedgers use futures as a form of insurance against price movements that could hurt their business or investments. These are often producers or consumers of commodities, or financial investors with large portfolios to protect. By locking in prices with futures, hedgers can stabilize their costs or revenues. For instance, consider an airline that will need 1 million gallons of jet fuel in six months. If the airline is worried that fuel prices might spike by then, it can buy fuel futures (or closely related crude oil futures) now to lock in the current price. When six months pass, if fuel prices have indeed shot up, the airline’s higher fuel costs are offset by gains in its futures position (which will have risen in value). Essentially, the futures profit helps pay for the more expensive fuel, hedging the price risk. If prices instead dropped, the airline would lose on the futures, but cheaper fuel in the market saves them money – the hedge did its job of smoothing out extreme outcomes.

Another example: a gold mining company might sell gold futures for future delivery of gold it has not mined yet. By doing so, it locks in the selling price for its future production. Even if gold prices fall later, the miner is protected because it already secured a higher price via the futures contract. Investors can hedge too – for example, an investor with a large stock portfolio could short stock index futures to guard against a market downturn (if the market falls, the gain on the short futures helps offset portfolio losses).

In summary, hedging with futures is all about reducing uncertainty. The hedger gives up some potential upside in exchange for avoiding potential downside. Futures are popular for hedging because they are efficient and liquid to trade, and they directly track the prices of the things businesses care about (commodities, interest rates, currencies, etc.). By using futures, companies can plan their finances without as much worry about volatile market swings.

Why Are Futures Popular in Financial Markets?

Futures play a crucial role in global markets and have become very popular for several reasons:

- Leverage and Capital Efficiency: Futures provide high leverage, meaning traders can control large positions with a relatively small amount of capital. This amplifies potential profits and lets people participate in markets (like oil, gold, or stock indices) without putting up the full value of the asset. For example, rather than paying $100,000 to buy stocks, a trader could use a few thousand dollars of margin to get exposure to the same $100,000 via stock index futures. Leverage increases the exposure and potential for gains, but it also heightens the risk of losses. When trading with leverage, always have a risk management plan in place.

- Liquidity and Price Discovery: Major futures markets are highly liquid, with many participants trading around the clock. This deep liquidity means it’s usually easy to enter or exit positions quickly. Moreover, futures trading contributes to price discovery – the process of finding the fair market price. Because futures reflect collective market expectations about the future, they provide valuable information. For instance, the futures price of corn for delivery next summer incorporates all known information and predictions about future supply and demand. Many view futures markets as leading indicators for commodity and financial prices.

- Flexibility (Long/Short & 24-Hour Trading): Futures make it straightforward to short the market or go long, so traders can profit or hedge in both rising and falling markets. This flexibility attracts traders who want strategies not just dependent on prices going up. Additionally, futures exchanges often have extended trading hours, sometimes nearly 24 hours a day, six days a week for globally traded contracts. Traders can respond to news and global events outside of normal stock market hours. For example, stock index futures trade almost all day during weekdays, providing a way to react to overnight developments. This around-the-clock aspect is a big advantage for active market participants.

- Diverse Asset Exposure: Futures exist for a wide array of asset classes. Traders can access markets that might be hard to trade directly. Want to bet on oil prices but don’t want to deal with storing barrels of oil? Oil futures make it easy. Interested in foreign currencies or stock indexes or metal prices? There are futures for all of these. You can even gain exposure to Bitcoin through futures without actually holding cryptocurrency directly. This diversity makes futures a versatile tool for portfolio diversification. Some assets (like certain commodities) are most practically traded via futures because the futures market is well-established and liquid for them.

- Standardization and Fairness: Because futures are standardized and exchange-traded, everyone plays by the same rules. The exchange’s clearinghouse guarantees the trades, which virtually eliminates counterparty default risk – you don’t have to worry about the person on the other side of the trade not honoring the deal. Prices are determined in a transparent auction market, driven by supply and demand. This fairness and regulation (in the U.S., for example, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission oversees futures markets) give traders confidence. In contrast, some other derivatives (like certain over-the-counter contracts) might carry higher credit risk or less transparency.

Overall, futures are popular because they combine risk management, flexibility, and access. They let the farmer sleep at night without worrying about price crashes, and let the speculator trade big with a small stake (and hopefully not lose sleep in the process!). They are a fundamental part of modern financial markets, enabling price stabilization for industries and opportunities for traders.

(Just remember: with great power (leverage) comes great responsibility – new traders should educate themselves and manage risks when venturing into futures.)

FAQs

What is a futures contract in simple terms?

It’s an agreement to buy or sell something at a set price on a future date. Think of it as locking in a price now for a purchase or sale later. For example, agreeing today to buy 100 barrels of oil for $70 each next month is a futures contract.

How is futures trading different from spot trading?

In spot trading, you buy or sell an asset for immediate delivery (you pay now and get the asset now). In futures trading, you’re dealing in contracts for future delivery. Also, futures use margin and leverage – you only pay a fraction of the asset’s value upfront – whereas spot trades usually require full payment. Another big difference is you can easily go short with futures (bet on price drops), while shorting in spot markets can be harder.

Why would someone trade futures instead of just buying the asset outright?

There are a few reasons. One is leverage – with futures you can control a large amount of an asset with a smaller investment (which can increase potential returns or losses). Another is the ability to short sell just as easily as buy, allowing profit from price drops or hedging of positions. Additionally, futures can be used to lock in prices (helpful for hedging) and often trade nearly 24/7, letting traders react to news anytime. Essentially, futures offer flexibility and efficiency that direct ownership might not.

What does it mean to go “long” or “short” in futures?

Going long means you buy a futures contract, expecting the price of the underlying asset to rise. If the price goes up, the value of your contract rises and you can sell for a profit. Going short means you sell a futures contract first (opening a short position), expecting the price to fall. If it does fall, you can buy back the contract at the lower price and pocket the difference as profit. Long = bet on price going up; Short = bet on price going down.

What is margin in futures trading?

Margin is like a security deposit or down payment you must put up to open a futures position. It’s only a fraction of the contract’s total value (typically around 3-12% of the value, depending on the asset’s volatility). The margin ensures you have some skin in the game and can cover losses. If the market moves against you, you may have to add more money (maintenance margin) to keep the position open. Using margin lets you leverage your trades.

Can I exit a futures trade before the expiration date?

Absolutely. You do not have to hold a futures contract until it expires. In fact, most traders close out their positions before expiry – either to take profits or cut losses, or simply to avoid dealing with settlement. You exit by taking the opposite position to what you originally did (if you bought to go long, you sell to close; if you went short, you buy to close). This offsets your contract obligation. Exiting early is standard practice – only a small percentage of contracts are ever held to expiration and settled by delivery.

Do I have to take physical delivery of the commodity or asset?

Not if you don’t want to. While some futures contracts can result in physical delivery, almost all individual traders close their positions or roll them over to future dates before that happens. Also, many futures (especially financial futures like stock indices) are cash-settled, meaning you just pay or receive the profit/loss in cash at expiration rather than delivering any goods. Physical delivery is more of a concern for commercial users.

What happens when a futures contract expires?

Upon expiration, if you haven’t closed the position, the contract will settle. Depending on the contract, either a cash settlement happens (the difference between your contract price and the final market price is calculated, and your account is credited or debited that amount) or physical delivery happens (the seller delivers the actual commodity to the buyer at the specified location). For example, a futures contract on a stock index will just cash-settle – you get the profit or loss in cash. A futures contract on wheat, if held to expiry, could mean the seller must deliver bushels of wheat to the buyer per the contract terms. Again, most traders don’t let it get to that point; they close their position or roll it over (switch to a later contract) before expiry.

What assets can I trade with futures contracts?

A wide variety! Futures began with commodities like grains and metals, but now you can trade futures on commodities (corn, soybeans, crude oil, gold, natural gas, coffee, etc.), stock indices (e.g. S&P 500, NASDAQ futures), currencies (like Euro, Yen, or Bitcoin in crypto futures), interest rates (bond and Treasury note futures), and more. There are even futures on things like weather or volatility indexes. Essentially, if an asset has a well-established market and many participants, there’s probably a futures contract for it. This lets you diversify – for instance, you can get into commodity markets without owning a farm or oil well, simply by trading futures.

How are futures prices determined relative to current prices?

A futures price is generally based on the spot price of the underlying asset, plus or minus adjustments for carrying costs and other factors. In other words, the market looks at today’s price and then factors in things like storage cost, insurance, and interest rates (for holding the asset until the future date), as well as expectations of future supply and demand. If it’s expensive to hold an asset (e.g. storage for commodities or interest cost for financial assets), futures for a date in the future might trade higher than the current spot price. Conversely, if people expect future supply to be plentiful or demand to drop, a futures price could be lower than today’s spot price. By expiration, though, the futures price will have converged to the spot price, because at that point they essentially become the same (the asset is being delivered or settled). So, futures prices are a reflection of the current price plus the market’s best guess of what carrying that asset into the future entails.